It was a balmy summer evening when I met Kumkum Devi working on a piece of cloth; doing intricate embroidery. She looked tired but her eyes were gleaming with satisfaction of design coming out as she wanted it. The colourful threads spooled around her as she deftly moved the needle in patterns that took me to my childhood. My mother used to embroider these same colourful stitch patterns on old fabrics to give them new life. As a child, I did not understand the importance of these traditional embroideries and never took an interest in learning them …

Origin And Meaning

If you happen to be in a quiet village of northern Bihar, you might find women with needles poised over colourful scraps of cloth. It is widely believed that the women of the village of Bhusra (in the Muzaffarpur district) had an idea as simple as it was profound: to gather old saris and dhotis, layer them together, and stitch them with a running stitch. These layered quilts were called Sujni.

“Su” meaning ease/facilitating, “Jani” meaning birth. So the quilt becomes the “facilitator of birth” – a gentle embrace for the baby in the form of swaddles. There is also a folklore attached to it. Long ago, in a hamlet by the river in northern Bihar, there was a goddess of torn and tattered cloth, Chitiriya Maa. The women believed that every fabric, no matter how worn or frayed, carried memories, lives lived, tears shed. If you stitch these pieces together, you stitch lives together, you heal. Thus, when a child was born, the mother wrapped them in a quilt of old fabrics, calling upon the goddess to bless the new life.

Women still make it for their children or grandchildren weaving every thread in anticipation of the new life. First they select the fabric, which can be anything from cotton to fine muslin. The design is drawn on the fabric using freehand drawing or a stencil with chalk. Next, embroider the design using different coloured threads and stitches like chain stitch and back stitch. The embroidery done entirely by hand is a laborious work taking 5 to 10 daysabout a week for the size of a single-bed sheet. After embroidery is done, the cloth is washed and ironed ready for use.

Image courtesy shringhaar.com

Motifs, Myth And Symbolism

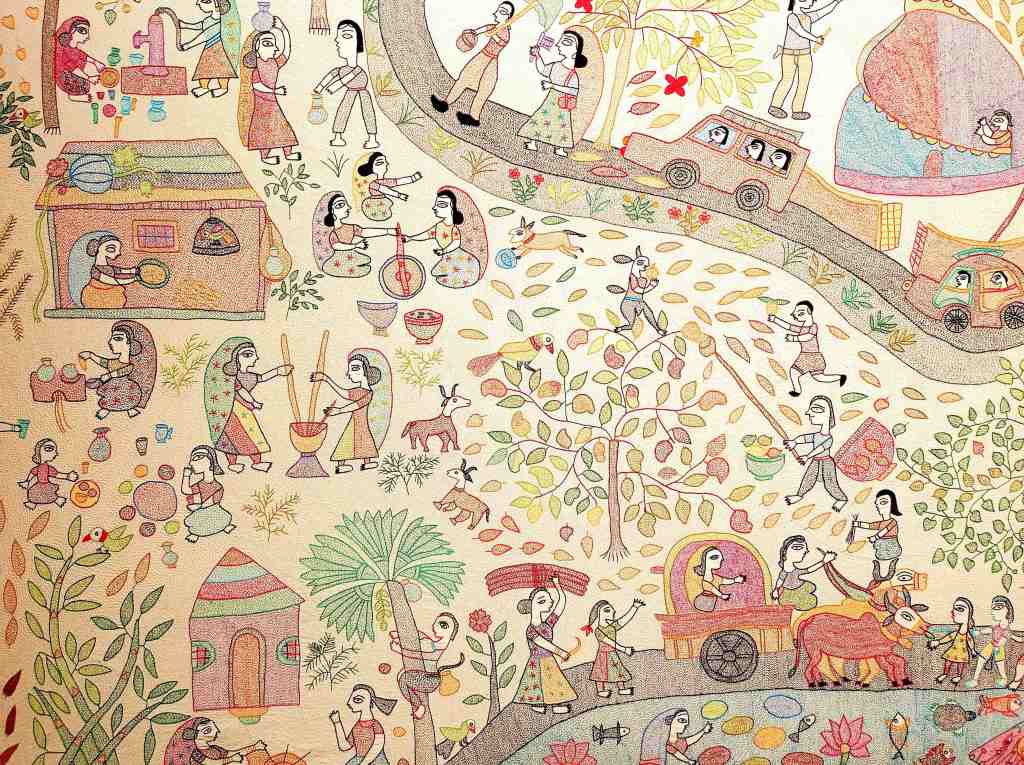

The craft is deceptively simple in tools, yet rich in expression. In Sujni quilts, the motifs are rich with meaning.

- Sun and cloud: Life giving forces. The sun in yellow thread, clouds in grey or white indicate fertility, renewal

- Sacred animals and mythic creatures: Elephants, birds, winged beings; protecting against evil forces

- Everyday scenes: Women at work, stoves, household utensils, village life. These give a sense of time and place

- Social narratives: In modern Sujni, scenes of drinking husbands, dowry violence, girls’ education emerge. The quilt becomes testimony then

Colours carry meaning too. Red for the life-blood, yellow for the sun. Dark outlines for protection. The Geographical Indication (GI) registration number for Sujni Art is 74, Class 26 under the GI Act, 21st September 2006.

Kumkum Devi is associated with Swasti Seva Samiti. Swasti is an organization based in Dalsingsarai (Samastipur district of Bihar), working with a group of women artisans who practice the craft. In 2014, founder Ms. Anita Chaudhary realised women had the skills but did not have the opportunity to showcase it to the world. Her motive was to fill the gap between this traditional art and market demands for the final product. Currently, twenty-six women are associated with the organization. Various exhibitions in Patna have showcased their work earning them appreciation and has found buyers as well.

I met some of the women associated with Swasti on a rainy evening. Over a cup of tea, these smiling women shared their stories of discovering the importance of their skills. Reeta Devi, learned the art from her mother as a child. As a young girl, she could not go outside too much; so she found herself restricted in taking her interest in Sujni forward; to learn further from her mother or practice it regularly. Then, her mother-in-law took her to the first meeting of Swasti.

“I discovered that this is not just a hobby but a creative journey which made me feel I can do something for myself.”

Reeta Devi, a Sujni artisan associated with Swasti Seva Samiti since 2016

Suman, one of the newest member of the organisation, got married at the young age of fourteen. She dreamt of a bright future, furthering her education, which halted. Early marriage life left no time and space to practice hobbies or learn crafts. Life handed her a lot of responsibilities at a very young age. After years now Swasti gave Suman another shot at her aspirations for herself.

“I struggled to study or work, but when exhibitions recognise our work and people appreciate my art, I feel like life has come full circle.”

Suman Devi joined Swasti Seva Samiti in 2024

From my conversation, I realised there are many reasons the art has got few takers. In villages, no one wants to buy them as almost everyone knows the art. Marketing and awareness is another reason that only few people know about the art form. There are few occasions like festivals when orders come otherwise the sale is lean throughout the year at the organisation. Another reason that art is dying because younger generations don’t want to learn this art form. The current generation invests in education and aims to settle into well-paying jobs.

Sujni art is an example of place based craft economy preserving producer identities. It uses minimal external resources to create durable products which are sustainable with a low carbon footprint. Despite their rich heritage and cultural relevance, the artisans struggle to get fair income and sustain their crafts. They struggle to adapt to the modern world while preserving their traditions and art form.

Sujni art is an example of place based craft economy preserving producer identities. It uses minimal external resources to create durable products which are sustainable with a low carbon footprint.

What Revival Entails

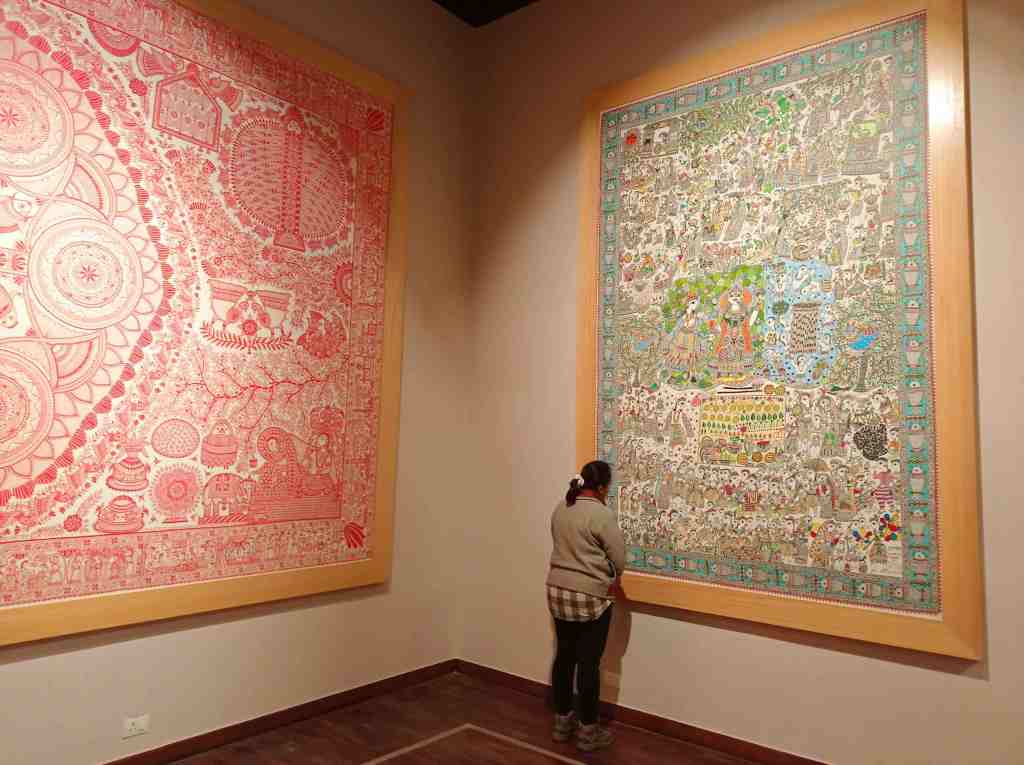

Though rooted deep, Sujni was on the verge of slipping into oblivion by the late twentieth century. The quilt for the newborn was less made as societal changes came. Then, around 1988, the organisation Mahila Vikas Sahyog Samiti (MVSS) helped revive the craft near Bhusra. Today, the craft is protected under a Geographical Indication (GI) tag. About six hundred women artisans in about twenty two villages around Muzaffarpur and Madhubani practise it. The craft has been adapted to bedspreads, wall-hangings, cushion covers, sarees, stoles and other textile products to increase its commercial value and move from craft to livelihood to ensure it sustains.

The GoI is actively working to preserve the craft traditions of the country. Craft clusters, GI tags, theme crafts are actively being promoted and worked on by the Ministry of Textiles. The government is working on creating market linkages, training youths to preserve and promote the crafts on national and international platforms. Initiatives like ‘Vocal for Local’ are aimed to promote indigenous local products. Yet, policy and reforms are not alone enough for preservation and continuation of rich craft forms of India. These crafts will be able to continue if there is a market and demand for these products.

The journey of a mother making a cozy blanket for baby to present times when these women are marking their identity as artisans, this art has come a long way from its origin but its essence remains the same. For the women, their skills and art has earned them an identity as artisans. A defining moment in their journeys came when their art went outside the confines of four walls of their homes. When they get the right channels to sell their products via collectives and exhibitions, they embark on their economic empowerment. Through training, product diversification, market linkages, social organisations like these are giving women the opportunity to build their twin identity – as a creator of an art and producer of livelihoods.

Further Reads & References

- More about Sujni art in this article by Shringhaar, written in September 2024

- Research paper in International Journal of Applied Social Science, written by Sweta Rajan Sharma and Meenakshi Gupta in September 2024

- You can buy products like blankets, bags, bedspreads, wall-hangings, cushion covers, sarees, stoles and gif-tables from Swasti. Contact: swastisevasamitimahilaekai@gmail.com, 7631626123

- Story: Nazreen Nazir who works as a public health communicator in Dalsinghsarai in Samastipur (Bihar), close to where Swasti Seva Samiti works

- Editor: Anupama Pain, Chabutra Team

Leave a comment