Degaon

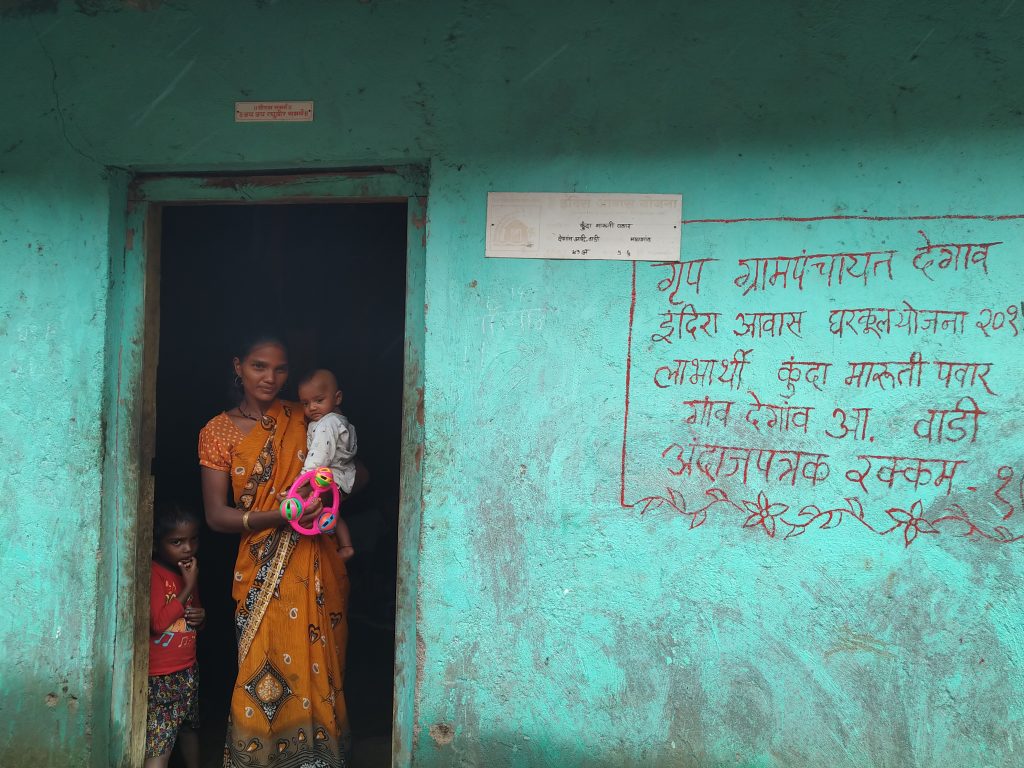

No one visited Degaon after evening, or for that matter, even during the day. No one visited Degaon ever, except for its inhabitants. As night fell, the village shut and packed itself into the forest and is reborn in the morning, the day after. Degaon was far across the stream, on a forest hill of the Sahyadri. It was not really a village, though there were a few hundred people living shabbily here and there alongside goats, dogs, cats, hens, squirrels, garden lizards, chameleons and harmless water snakes. The men of Degaon were bare bodied with stretched temples and chiseled jawlines. The women were skinny and chewed betel nut all day. Their children were naked and malnourished.

Every morning, the men and women would go down the hill in search of work. You can find them squatting in the bazaar under the shade of trees or lazing on the entrance steps of the municipal office, talking to each other in hushed tones. Contractors with handbags clutched in their armpits walked by the bazaar and picked up people for labour. They would go with them. Sometimes no one came and they spent their day sipping tea, gossiping and trying to fit in a society that doesn’t want them. By evening, they start walking back up the hill, with pockets full or empty, never in between, and reach their homes in Degaon by sun down.

Each time I go to Degaon, my eye catches something that I missed the last time. As I tried to maneuver the bike on the rocky trail towards Degaon, I was extremely cautious. Insects jumped straight at my face, bats circled above and the cicadas went on and on into the night. When we finally reached the top of the hill, it was pitch dark. The bike’s headlight startled a few goats. A dog, lying flat on the path, lifted its head without waking up, to look at us. I killed the engine and looked around. It took a while for my eyes to get adjusted to the darkness. My colleague called out a name and a man came quickly with two chairs. I paced a few steps to see the houses that I saw in the morning previously, now lifeless.

An old man with a stick walked up to us and stood beside us. He scratched around his chest as he spoke. Bhuvan dada* was a senior member of the village and the Gavki (a traditional tribal forum for discussion and debate that happens in the hamlets). He was about 70 years old and had a sharp eyesight. After enquiring if we had reached safely, he said that he had visited the local political party office today to meet the office bearers. The state elections were scheduled this month.

My colleague asked, “Kai dada, paise paije tumala?” (Do you want money?)

Bhuvan dada said, “Mala paise nai paije, mala vikas paije” (I do not want money, I want development)

He then went around slowly, calling people. Soon enough, people assembled and we went into the room reserved for Gavki.

*Name changed to protect identity

During my initial days in Raigad district of Maharashtra, I could not believe that people lived in such extreme poverty so close to urban mega cities and still somehow go unnoticed. I started looking up the development indices.

As per census 2011, Maharashtra has a population of 11.42 crore of which 9.35% are tribals, categorized as Scheduled Tribes (ST). Maharashtra has the second largest tribal population in the country. Raigad has 26.3 lakh people, of which 11.58% are tribals. That’s about a little more than 3 lakh. More than 80% of them are Katkaris.

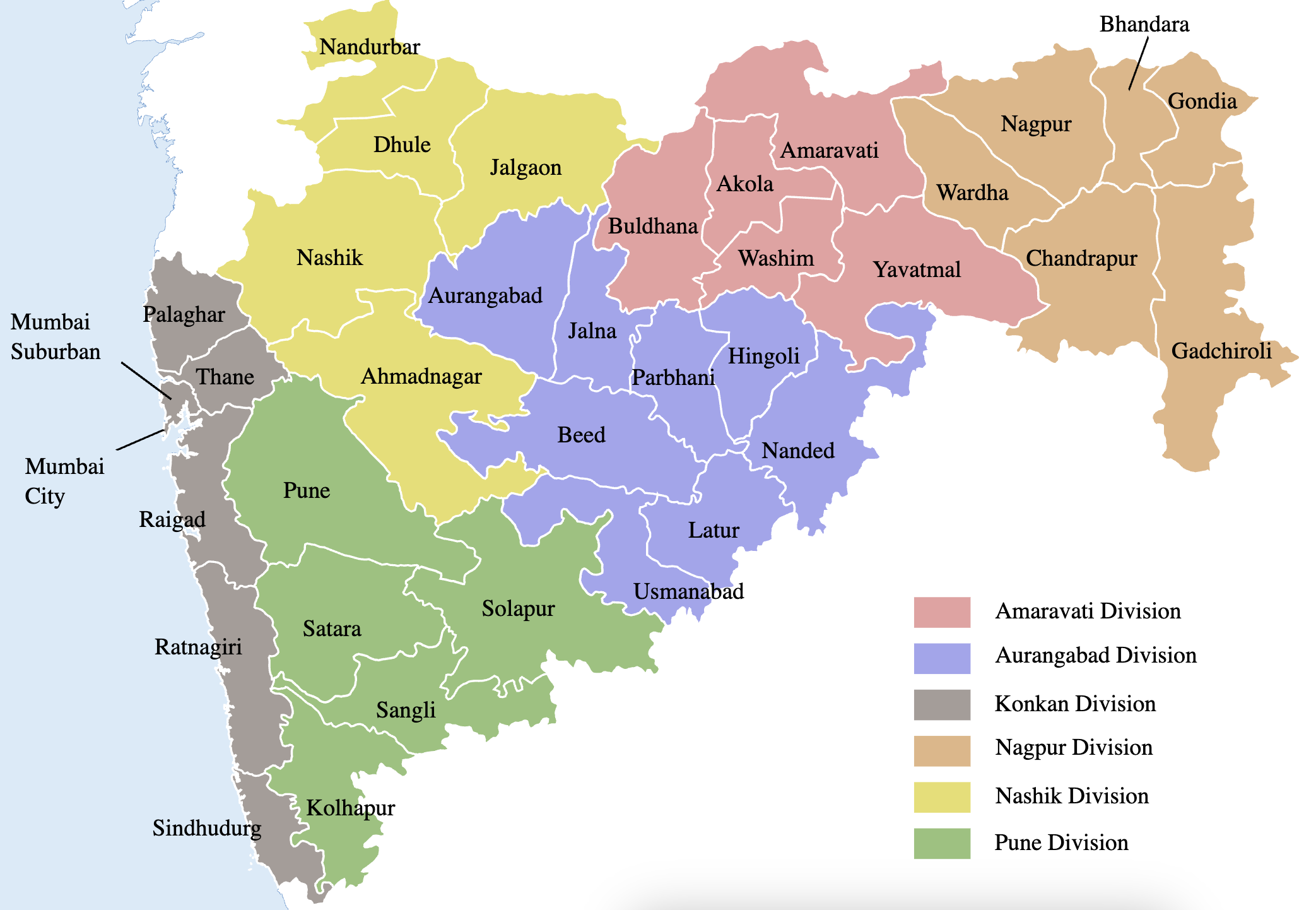

Raigad, the first capital of the former Maratha Empire, the land of captivating forts and free flowing streams; the home to picturesque Konkan belt where tribals stay dormant deep inside jungles, as if incongruous. Raigad in Maharashtra is surrounded by Thane and Navi Mumbai on the north, Pune and Ratnagiri on the east and south respectively while the Arabian Sea gently rests on the west. The city starts where the hustle of Mumbai ends. Or perhaps Mumbai begins where the rustic charm of Raigad ends. It is spread out into 4 sub divisions for administrative convenience, with 15 talukas and 1967 villages.

Maharashtra has a population of 11.42 crore of which 9.35% are tribals, categorized as Scheduled Tribes (ST). Maharashtra has the second largest tribal population in the country. Raigad has 26.3 lakh people, of which 11.58% are tribals. That’s about a little more than 3 lakh. More than 80% of them are Katkaris.

2011, Census Data

The Katkari tribes are located primarily in Raigad and in parts of Palghar, Ratnagiri and Thane districts as well and in some places of Gujarat.

Sub-classification

Katkaris are former criminal tribes under the Criminal Tribes Act, 1871, an inhuman piece of legislation enforced during the British rule. The act describes certain groups of people as ‘habitually criminal’ and puts restrictions on their movements which led to alienation, stereotyping and harassment, to say the least. After independence, the Act was repealed resulting in more than 20 lakh tribal people across the country being decriminalized. However, the stigma associated with the act continues to haunt the Katkaris to this day.

Presently, the Katkaris are classified as Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups, 2006. The Government of India came up with this classification to introduce targeted interventions noting that some tribal groups had the least development indices as compared to other tribal groups. The criteria used by the state for classifying PVTGs was as follows:

- A pre-agricultural system of existence such as hunting, gathering

- Zero or negative population growth

- Extreme low level of literacy in comparison with other tribal groups

- A subsistence level of economy

Groups that satisfied any one of the above criterion were considered a PVTG. There are more than 700 tribal groups in India and 75 are classified as PVTG. Maharashtra is the fastest growing state in India. Its GDP exceeds ~450 billion USD and for comparison, the second in line is Tamil Nadu, much behind at a GDP of ~270 billion USD. As of 2011, Maharashtra’s HDI was 0.752. Raigad’s HDI in the same period was 0.759. Now, that’s higher than the state’s! Data master, Hans Rosling said,

“It is dangerous to look at average data because often there is a huge difference within.“

Lifestyle

Katkaris were historically forest dwellers. The name Katkari is derived from a forest based activity – the making and barter or sale of kath (Katechu) from the khair tree (Acacia Katechu). It is produced by boiling wood from the khair tree and evaporating the resulting brew. This makes an astringent used in Ayurvedic medicine and in mixtures chewed with betel leaves.

The Katkaris were also one of the few tribal communities of India that consumed rodents. However, it is not clear if this practice still continues. The most common surname in the community is Waghmare which means ‘tiger slayer’. They are bilingual, speaking the Katkari language amongst themselves and Marathi with others. A few of them speak Hindi as well. Today, most Katkaris have migrated from their forest dwellings to the plains; while some hamlets are located on the hills.

Almost every tribal hamlet is located on the boundary of the main non-tribal part of a village. These tribal hamlets are suffixed with the term ‘Adivasi’. For example, Warak Wadi and Warak Adivasiwadi. The village cement road ends where the Adivasiwadi begins and seldom has water connection and/or electricity. Schools and community centers are also located in the main village. This is an indication of physical exclusion.

Landlessness

The Katkaris are plagued with the issue of landlessness and subsequent distress migration. Most literature on the Katkaris cite landlessness as the single biggest problem making them vulnerable and deprived. The landless rate of 87% among the Katkari is much higher than 48% for rural households in India as a whole. The Forest Rights Act, 2006 rules that traditional forest dwellers shall have the right to hold and live in forest land under the individual or common occupation for habitation or for self-cultivation for livelihood. Despite over years into force, only 13% of the Katkaris have been assigned forest land. As a result of landlessness, migration is rampant and livelihoods are seasonal.

Topping everything, Katkaris face eviction of all forms. The rapid rise of Mumbai and surrounding areas led to skyrocketing land prices. This led to landholders selling off land to corporates and developers. This land is in close quarters to tribal settlements and tribals are constantly intimidated to move to different locations.

During the agricultural season of May to October, they work as farm labourers in the fields of Marathas which they deem as their golden period of the year. They earn a wage of Rs. 350-400 per day along with lunch and tea.

They also catch fish and crabs during this season which they sell in the nearby towns. Some income also comes from minor forest produce. The image is of a pulsating fish market in Raigad town.

Known for their physical strength and endurance, the Katkari comprise a large part of the workforce in the regional brick-making industry, contributing literally brick by brick to the rising cityscapes of Greater Mumbai. This work, occupies about 60% of the Katkari families in Raigad and Thane districts (Buckles & Khedkar, 2013).

Katkari men, women, and children migrate to work sites, often for 6 months each year from November to April, leaving their hamlets virtually abandoned. Bonded labor is prevalent and living conditions are dismal.

The PM JANMAN Mission was launched on Janjatiya Gaurav Divas on 15th November, 2023 with a resolve to reach out to the PVTGs, most of whom still dwell in the forests.

Further Reads & References

- A photo story of the Katkari by the Cambodian freelancer Miguel Jeronimo, 2024

- The PM JANMAN Mission details, part of the Ministry of Tribal Affairs, 2023

- Socio-Economic Issues Facing Katkaris by Tata Institute of Social Sciences in Mumbai, 2014

- Fighting Eviction: Tribal Land Rights and Research-In-Action by Buckles D. & Khedkar R., 2013

- Story: Nikhil Kanakamedala who worked for a year in 2019-20 in Raigad in Maharashtra

- Editor: Anupama Pain, Chabutra Team

Leave a comment